Green Blue Grey Infrastructure participatory design with marginalised communities

The aim of my RECLAIM secondment with Spelthorne Borough Council was to engage the wider community in the borough to establish a strong GBGI baseline for assessing the impacts of emerging developments, including Heathrow expansion and the River Thames Scheme.

After successfully contributing to the inclusion of a Green Corridor policy within Neighbourhood Planning through a community led participatory process (Figure 1), I was keen to explore how the participatory process can be scaled-up to the local authority level, so I enthusiastically took up the RECLAIM secondment opportunity to work with community members and Spelthorne Borough Council officers. The aim of the secondment was to lead a participatory approach that would feed into the emerging Local Plan and engage with the needs and desires of local community members, especially low-income and vulnerable groups.

Figure 1: Map from the Ascot, Sunninghill and Sunningdale Neighbourhood Plan[1] highlighting the green corridors identified through a participatory process.

[1] Ascot, Sunninghill and Sunningdale Neighbourhood Plan (2014) Url: https://www.rbwm.gov.uk/home/planning-and-building-control/planning-policy/ascot-sunninghill-and-sunningdale-neighbourhood-plan

But first, a little bit about my background to provide some context. I am a Senior Lecturer in Environmental Information Systems at the Open University. When I turned 50, two years ago, I went part-time because I wanted to work more directly with communities. In May 2022, I was elected as a councillor within Runnymede Borough Council which gives me an opportunity to understand and influence local policy making, especially with regards to GBGI, sustainability, and climate change. But I'm also a co-director of a community interest company, called the Cobra Collective, that's focused on enabling lesser heard voices to share their experiences and gain greater agency. My RECLAIM secondment was through the Cobra Collective.

As the objective of this secondment was to see if we could scale up the participatory process up to the borough level and beyond, it was useful to see where community engagement processes were already mentioned in local authority GBGI policy. For example, Surrey County Council's principles for GBI [2] include:

“Principle 6: Planned inclusively and collaboratively

Create opportunities to engage communities and landowners in the planning, creation, enhancement, delivery and maintenance of nature-based solutions. Local involvement will embed green and blue infrastructure into the community and lead to better design and maintenance.”

Principle 7: Public benefit for all

Green and blue infrastructure must deliver public benefits for all both directly and indirectly, including recreational and health and wellbeing benefits. Interventions to achieve public benefits should consider the needs of all social groups to ensure inclusivity.”

[2] Surrey County Council (2022) Green and blue infrastructure: best practice and case studies. Url: https://www.surreycc.gov.uk/community/climate-change/what-are-we-doing/green-and-blue-infrastructure

These principles therefore require processes for community engagement and the need to demonstrate direct community benefits, with the reference to “all social groups” strongly suggesting that the needs and aspirations of marginalised groups are paramount, especially given that it is these groups that have the least access to green spaces. However, in my review of local authority practices, I struggled to see example of participatory and inclusive process implemented in practice. Instead, I repeatedly came across example of GBGI policies developed and implemented in a top-down way. The only process of community engagement, if at all, was a period of consultation on a near-final document published on a website, with only a few weeks to provide comments, but that is as far as it goes: no facilitated processes, no co-design, no assessment of community impact, especially on the most vulnerable.

So, the secondment was an opportunity to radically change the approach, and this was perfectly in line with RECLAIM Network’s objectives to promote multi-functionality, systems thinking, embedding aesthetics and people’s needs into GBGI design in order to maximise buy-in. We needed to go beyond the siloed top-down approach that many GBGI professionals use. For example, one of the main challenges that I had in the secondment was trying to work with officers that only had climate change or biodiversity or community services under their remit. We really needed much more joined-up thinking across departments.

The RECLAIM Network secondment provided £3,000 of funding for my 20-days of work with Spelthorne Borough Council. It didn't cover my time which I provided in-kind, but it did cover the costs of bringing in experts (including a professional participatory video trainer), hiring a workshop venue, and paying for participants' travel expenses. But because of the scale of the task, I also had to seek other sources of funding to drive this. The Local Government Association, in collaboration with UCL, through their Net Zero Innovation Programme, also gave £12,000 for a ‘Community-led Climate Initiative’ process. The Open University also involved Spelthorne in a project aimed at local authority policy change towards climate-resilient agri-food systems. All these additional sources of support helped the overall engagement process.

The partners in the community engagement process were Spelthorne Borough Council and, crucially, the Talking Tree Climate Emergency Centre. Talking Tree operates out of a shop on Staines High Street made available by Spelthorne Borough Council. This was the hub through which all of our community engagement workshops and meetings were carried out. It was absolutely crucial to have a community-based entity like Talking Tree supporting this. The Open University supported aspects of the projects, through, for example, paying for Talking Tree facilitators, and I also had a lot of help from local biodiversity specialists.

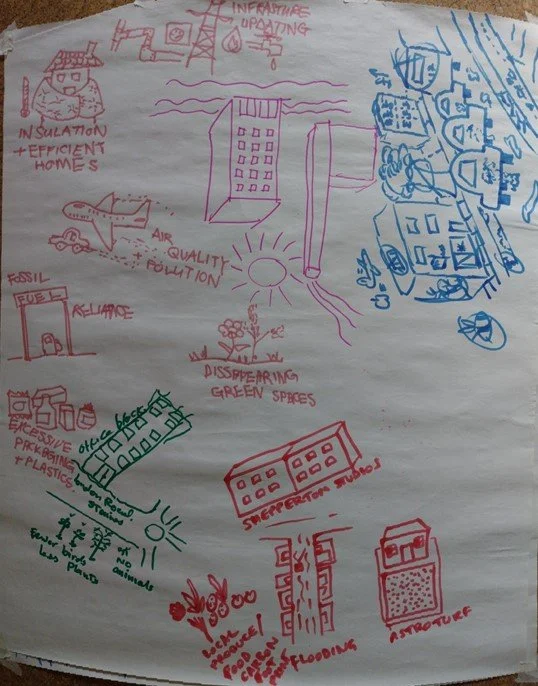

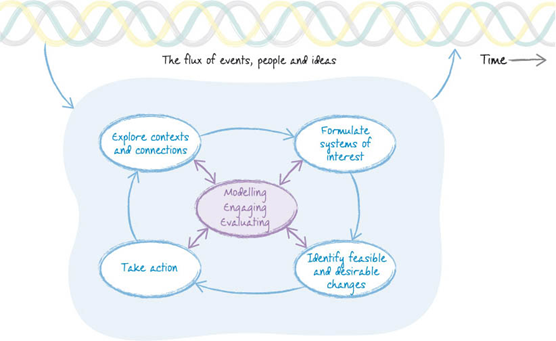

The process involved a very transdisciplinary and holistic approach inspired by Soft Systems Methodology[3] (SSM). This approach is used to work through complex challenges and has been successfully applied all over the world. You start off SSM with exploring the context and the issues at play. One of the big issues that we have as professionals when we support community members in deliberations is that you can't dive straight in asking: "Well what do you think about GBI in your area?" First of all, most community members, especially from under-represented backgrounds, have never heard of the term ‘green and blue infrastructure’. So you've got to start from where they are at, their concerns and their interests. And the easiest way to start from where they're at is to get them to explore their challenges. One of the key exploratory techniques used in SSM is the ‘rich picture’ technique, where participants are involved in drawing a collective visual representation of the issues at hand (Figure 4).

[3] Soft Systems Methodology is a powerful participatory process used to tackle complex real-world problems, and has been taught for over 30 years at The Open University. See the following introduction to the process: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=65641§ion=6

Figure 3: An example of a rich picture drawn by participants to explore the challenges experienced in Spelthorne.

The next step in the SSM process is that you look at the interests that various stakeholders have in the situation and try to mediate between these various interests. In this case, our focus was very much on mediating between the interests and actions championed by community members, and the limitations and constraints of Spelthorne Borough Council, who were represented in the workshops by two officers. You then get to a phase where you support participants in identifying a range of feasible and desirable interventions, which are refined down to one or more practical intervention, and then finally you take action, learn lessons, evaluate impact, and then re-explore how the context has changed in an ongoing action learning cycle (Figure 4).

Figure 4: A simplified framework capturing the essence of the Soft Systems Methodology process, as taught by The Open University in its postgraduate module on Environmental Decision Making.

However, one of the big issues with community engagement processes is that often you have a fantastic time in workshops, people come up with great ideas, but very soon that social memory of deliberations is lost. So, by the time you get down to the next workshop, some people have forgotten what has been discussed, there are new participants coming in, or some participants may not have been able to attend a particular workshop because of other engagements but are still committed to the process. So, it was absolutely crucial to use participatory video to record proceedings. This was not only important for dissemination in the public domain, but also to act as a digital social memory for the process to-date. Every time we had a community workshop, we therefore carried out a screening of the highlights of the previous workshop so people could come up to speed which the deliberations so far. The participatory videomaking was led by a ‘Youth Digital Eco Warrior Team’ which was trained by me and Claudia Nuzzo - an expert participatory video facilitator also from the Cobra Collective.

It’s important to highlight here that the participatory video process has a very powerful intergenerational impact in that, generally, it's very difficult to engage youth in policy deliberations, particularly when mixing with adults. But, enabling them to play an important role in the process, especially something exciting and fun like digital storytelling and video making, was a way for them to be at the centre of the process. This gave the young videographers the opportunity to ask questions and engage in dialogue with participants from all walks of life, and for their work to be recognized and valorised by the wider community.

We had an average of 30 participants in the 6 workshops that underpinned the main part of the engagement process, with a strong representation from ethnic minorities and low-income groups. About half of the participants accepted the £20 reimbursement for their travel expenses at every workshop. This was a key strategy for enabling those that would otherwise not be in a position to participate.

As we worked through the SSM stages in the workshops, the key community priorities that emerged was that many participants wanted to focus on delivering practical and immediate interventions within microsites. One of the big issues as academics, practitioners and policy makers, is that we have a tendency to focus on the big strategic picture, whereas communities really felt that they had very little control and say at that level, whereas they felt greater agency when dealing with much smaller ‘microsites’ such as grass verges and abandoned corner plots on their estate. That came out very powerfully in the participatory process. Even more significant was their urgency in seeing direct and immediate benefits when intervening within these microsites. They required interventions to address their cost-of-living challenges and mitigate air pollution.

We often talk about multifunctional GBGI, but these multi-functional properties are abstract benefits to communities. Participants wanted to know: "Well what's it going to do for me right now in my community?" One very practical request that came through was that green spaces within the borough are often maintained as just low-cut grass and the question that emerged about these spaces was: “Can we grow food there?” and “Can we rewild them to remove air pollutants?” In other words, what are the immediate, tangible benefits for the most marginalised that we can deliver right away?

The main challenge I had, on the other hand, was accessing the very basic data from Spelthorne Borough Council, including maps and reports, in order to support the deliberation process in the workshops. I found that there's almost a firewall between officers and people like me that want to support communities in deliberations. Repeated requests for maps and reports were met with promises but no action, often with the reason that these could not be shared in the public domain. So we were faced with significant constraints in understanding Spelthorne Borough Council’s strategy and what baseline data, if any, they were basing their GBGI decisions on. So we actually went about doing our own baseline data collection, using Google Earth to map out accessible microsites, and tools such as i-Tree Canopy[4] to assess the overall level of ecosystem services provided by GBGI in Spelthorne.

[4] https://canopy.itreetools.org/

Another big issue is that officers were under significant constraints with regards to resourcing. The overall strategy in many local authorities nowadays is to identify cost savings, rather than additional expenses. So, although never explicitly mentioned, you have the sense that the underlying objective for community participation is to see if the process can result in community members tacking over some tasks so that less council staff time and resources can be used. Could, for example, communities take over green spaces so that the council does not have to maintain it themselves?

A final major challenge encountered was with the political cycle. This was a big hindrance in moving things forward. The ‘purdah’ period during elections in April meant that, basically, no strategic decisions could be made at council level. And once the elections were over, the significant turn-over in elected councillors meant that there were further delays in decision-making. Indeed, on June 6th 2023, elected councillors voted 20 to 13 to pause the Local Plan process by three months in order to allow newly elected councillors to come up to speed with it[5].

[5] https://www.getsurrey.co.uk/news/surrey-news/spelthornes-9000-homes-plan-paused-27075281

In conclusion, progress with secondment objectives has been great with communities: we've had a series of very engaging and successful workshops, we've produced videos of the process, we've mapped microsites and we have started our first microsite intervention, transforming a derelict green space handed over by South Western Railways to the community. On the other hand, influence on policy within the council has been glacially slow. We have shown that the participatory process inspired by Soft Systems Methodology can be successfully and effectively deployed to support and sustain community engagement. But the corresponding engagement from the council has been limited. Although I have far exceeded my 20 days on the secondment, I am still committed to finishing the job. My next steps are to engage with key decision makers at council level and explore how we can integrate the very real needs and aspirations expressed by the community into GBGI policy and action.

This work has been supported by the UKRI-funded RECLAIM Network Plus grant (EP/W034034/1).

By Andrea Berardi, Co-Director at Cobra Collective.